Government to go for unused land held by public institutions to boost food production, but questions linger

By NLM Writer

The government plans to lease out underutilised land held by public institutions to the private sector for large-scale agricultural commercialisation, but questions linger given past experiences with similar programmes.

In total, the Land Commercialisation Initiative (LCI), being carried out under Flagship 4 of the Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy (ASTGS 2019 – 2029), targets to net 500,000 acres, which will be leased to the private sector for between five and 30 years for food production.

In 2013, the newly-inaugurated Jubilee promised to “put a million acres of land under modern irrigation and further expand agricultural production by employing modern technology on currently cultivated land and on the 2.5 million acres presently not in use” within five years. They had also promised to “make it easy for Kenyans to lease agricultural land and provide extension services.”

Of the targeted 500,000 acres, the Ministry of Agriculture claims to have already secured some 150,063 acres from five state corporations namely, the Kerio Valley Development Authority (KVDA) in Arror, Lower Turkwell I & II, Agriculture Development Corporation (ADC) in Trans Nzoia and Trans Nzoia Assorted, Tana and Athi Rivers Development Authority (TARDA) in Kiambere, National Irrigation Authority (NIA) in Bura I & II, Rahole I & II and Katilu I & II, and the University of Nairobi.

The plan, which is being supported by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC), is already at an advanced stage as the cabinet has already approved it, and the Land Leasing Framework, developed with the guidance of the Office of the Attorney General, was validated in November 2021.

‘Idle’ public and communal land

“Conservatively, 2.5 million acres of arable land, held by public institutions, largely remain unused. This can further be compounded by private and communal land owners,” the State Department for Crops Development, the driver of the initiative, says in one of the presentations seen by the Nairobi Law Monthly.

“In the short run, ASTGS seeks to unlock at least 50 large farms of more than 2,500 acres each with over 150,000 acres to be put under crop production,” the presentation adds.

IFC is supporting the design and initial implementation of LCI “by assisting the Government of Kenya in identifying viable land plots, organising and presenting plots for interested investors to evaluate, and implementing an approach to leasing and awarding the land in a transparent and organised manner.”

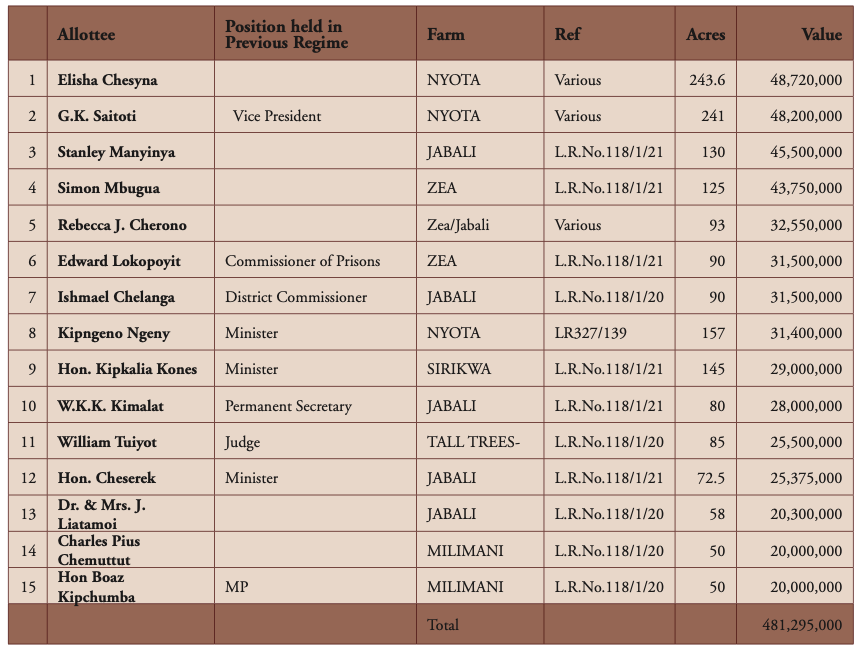

Noble and futuristic as the programme sounds, myriad challenges could beset it, the foremost being the experience of state corporations who, in the past, lost their land to well-connected individuals during the KANU regime.

One that quickly comes to mind is ADC. The corporations lost vast tracts of land across the country through the connivance of the then Commissioner of Land and influential individuals in the Moi government.

When he appeared before the National Assembly’s Public Investments Committee on Social Services Administration and Agriculture, ADC acting managing director Mohammed Bulle narrated how the corporation lost tens of thousands of acres of land to powerful figures in the Moi government, including the 32,000-acre Ngata land in Nakuru County.

Given up the fight

“What we have gone through is not a good experience. It has been extremely difficult to recover these chunks of land,” Mr Bulle told the committee.

“We have an individual who was allocated 6,000 acres and another 10,000 acres and who have not paid for the property…The Ngata farm, measuring 32,000 acres, is a clear case where the land was dished out to powerful individuals. We cannot salvage that land,” he added.

In Malindi, unscrupulous individuals subdivided ADC land into five-acre plots, notwithstanding the fact that ADC still holds the title deed for the property.

Like LCI, the initial intentions of the programmes were noble – including the resettlement of squatters – but ended up as a land-grabbing avenue that was exploited by well-connected individuals, who either paid the corporations peanuts or nothing at all. The grabbers then sold off the lands.

The Commission of Inquiry into the Illegal/Irregular Allocation of Public Land, which is popularly known as the Ndungu Commission after the name of its Chairperson, Paul Ndungu, made findings about how state corporations lost land through ‘noble’ government programmes or outright grabbing.

“The Commission found that state corporations’ land was illegally allocated to individuals or companies, disregarding the law and public interest. The allocation of corporation land was made in favour of ‘politically correct’ individuals in the former regimes,” the Ndungu Commission stated in their report.

“The development objectives for which the state corporation had been established were severely compromised, thus costing the taxpayer dearly,” the Commission added.

Ironically, the LCI has not referenced these past experiences of state corporations in their write-up for implementing LCI. There is no acknowledgement of these past land grabs, nor do they create any strong safeguards against a repeat of what happened in the past.

The only provision is that “land and any asset on it reverts to the government/landowner at the end of the lease period.”

The Ministry of Agriculture will need to do more to make the LCI watertight and not an avenue for grabbers to exploit to deprive state corporations of land.

Government business is bad business

Moreover, the Galana Kulalu Food Security project in Malindi is a fresh reminder of what happens when the government gets involved in agribusiness. Billed as a flagship project to “start an agricultural revolution”, as captured in the 2013 Jubilee manifesto, Galana Kulalu failed to achieve the targets.

It was unclear if the government, through the National Irrigation Authority, was running it or the Israeli firm, Green Arava. Several explanations have been offered since, with the 10,000-acre model farm the current and only response offered to a less successful project. This has bred a lack of trust in the government by the public and investors alike.

In the meantime, ADC has recently been under pressure to explain how they leased portions of Galana Ranch to institutions without documented agreements. For instance, Nyumba Kubwa Foundation (Mombasa Cement) is reportedly carrying out commercial activities on the ranch, yet there is no written agreement for the same with ADC.

Will LCI face a fate similar to the Galana-Kulalu Food Security Project?

‘Free for grabs’

In the haste to bring 500,000 acres into the hands of the private sector to engage in agribusiness, the drivers of the land commercialisation initiative have failed to define the keyword in the project, ‘underutilised land’. In some instances, officers from the State Department talk of ‘idle land’.

If an institution has land that it is not currently using but intends to put it to good use in the future when resources become available, would that make the land ‘underutilised? What would happen if the institution’s chief executive officer refused to let go of the land as required by the government? Will the institutions be forced to surrender the land as demanded? If that were to happen, how would the rights of the title holders be protected? These questions will warrant clear answers from the State Department of Crop Development and the IFC, which is a strong supporter of the initiative.

Excluded key stakeholders

Yet another drawback of the LCI project is that they left out other key institutions while developing the policy documents, such as the leasing framework, standard operating procedures and other key guiding documents.

A technical working group (TWG), as initially set up, had representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, the Agriculture Transformation Office, the Directorate of Veterinary Services, the State Counsel, the Ministry of Water and Sanitation, the Ministry of Lands, Public Works, Housing & Urban Development, Agricultural Development Corporation, FAO and IFC

among others.

It is only now that LCI is attempting to walk back and incorporate other key stakeholders, such as the National Land Commission (NLC), which constitutionally approves all transactions on public land.